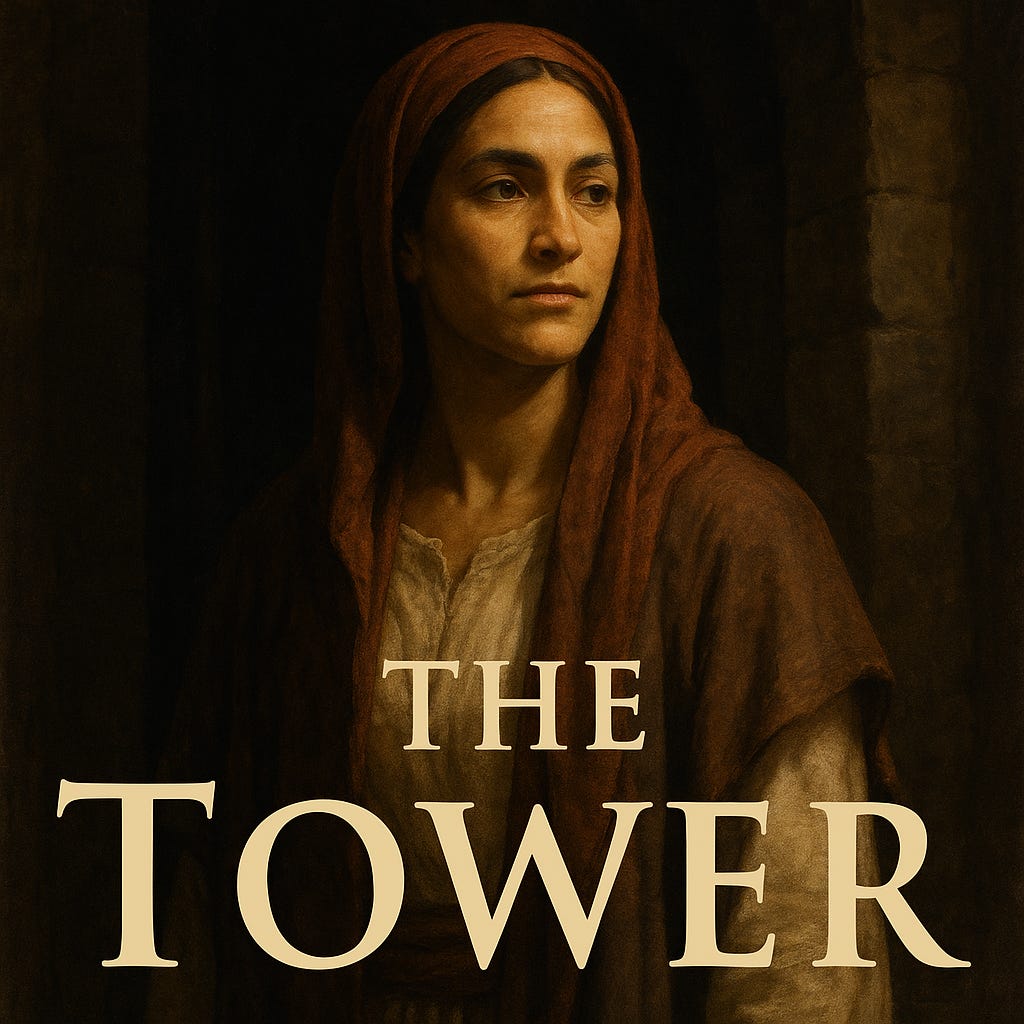

Was “Magdalene” a Title? Rethinking the Tower

Reclaiming Mary not as a hometown girl, but as a named and initiated witness to the mystery

What if Mary Magdalene wasn’t from Magdala?

That’s the question that, once asked, refuses to sit quietly in the corner. It has the power to reorder nearly everything we think we know about her—and about the early Jesus movement itself. For centuries, Christians have assumed that “Magdalene” was a geographical surname, identifying Mary as a woman from the town of Magdala, a fishing village on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. But what if “Magdalene” was never a place? What if it was a title?

A title like “The Rock.” Or “The Twin.”

A title like “Peter”—given by Jesus to Simon as a signal of spiritual commissioning.

A title like “Magdalene”—from Migdal, the Hebrew word for tower.

Suddenly, we’re not looking at a hometown. We’re looking at a declaration. A name that says: this one stands tall. This one sees. This one holds.

And once we entertain this possibility, we’re not just correcting a historical oversight—we’re peering into a veiled layer of the Christian story, where initiation, transmission, and recognition unfold not just in secret rooms, but in the names themselves.

Magdalene the Tower

Margaret Starbird was among the first in recent memory to raise the possibility that Magdalene might be something more than a hometown. In her 1993 book The Woman with the Alabaster Jar, she noted that the word Migdal in Aramaic and Hebrew means “tower”—a metaphor rich with connotation in mystical, prophetic, and erotic texts.

In the Hebrew Bible, towers are strongholds, lookout posts, pillars of clarity and protection. The Song of Songs, often linked to Mary Magdalene in Christian mysticism, refers to the woman as “a tower of David,” adorned with shields, resolute and beautiful. To call someone “the tower” was not casual.

If Jesus called her Magdalene, what was he naming in her?

Was it her constancy at the cross? Her vision at the tomb? Her willingness to anoint him for death while the others argued over the cost of the perfume?

A nickname often reveals the relational truth that titles obscure. The Rock was rash and blustering—until he wasn’t. The Twin (Thomas) carried the wound of doubt so others could see through it. And Magdalene? She held her station, unwavering, even when the sky went dark and the tombstone sealed.

If Magdalene is a title, then the woman we meet at the cross, the tomb, and the garden is not merely Mary from somewhere—she is Mary become something.

The Spiritual Function of Naming

In many wisdom traditions, names are not labels. They’re recognitions. To be renamed is to be seen, commissioned, transfigured.

In Sufi lineages, one receives a name after a spiritual breakthrough or transmission. In monastic Christianity, new names often accompany vows. Even in the Gospels, Jesus renames Simon as Peter—Petros, the rock—when Simon’s inner capacity to recognize Christ reveals his true nature.

Might “Magdalene” follow the same pattern?

It’s not just plausible. It’s pattern-consistent.

We have no early textual references that identify a town called “Magdala” as her home. While such a place did exist, it wasn't known as Magdala until centuries later. The earliest Gospel references never describe Mary as “from” Magdala. They simply call her Mary the Magdalene—as if Magdalene were a title known to the hearers, like a role or station.

In Through Holy Week with Mary Magdalene, Cynthia Bourgeault offers an intriguing suggestion: that Magdalene was “not a place name at all, but something like a nickname”—a name for one whose presence had become towering, whose vision had become wide, whose heart had become stable enough to endure the full arc of Jesus’s Passion without fleeing.

Such names are not given lightly.

A New Reading of the Texts

Once we remove the hometown assumption, new interpretive doors open.

What if the “Mary Magdalene” at the resurrection is not merely a grateful follower but the initiated witness—the one with eyes to see?

What if her naming was not incidental but intentional?

She was the one who stayed when others fled.

She was the one who anointed when others argued.

She was the one who recognized the Risen One in the garden—not because he looked the same, but because she had become what he was.

In mystical language, this is called recognition-through-participation. The “eye of the heart” sees because it has become what it sees. And it was this seeing that earned her the name. Magdalene.

Magdalene as Archetype: Tower of Witness

To read “Magdalene” as a title is to recover her stature—both literal and spiritual. She becomes not merely a footnote in the Passion, but a pillar of the early Church’s mystical memory.

In Cynthia Bourgeault’s language, she is “the gatekeeper of the Paschal Mystery,” the witness who shows us how to walk through death and transformation not as a victim of cruelty but as a practitioner of love.

And the tower metaphor goes deeper still.

In contemplative terms, a tower offers stillness and clarity, perspective and protection. It’s a structure built to see from. To stand tall in the storm. To witness.

That’s exactly what Magdalene does.

She sees what the others cannot.

She stays when the others scatter.

She names him when he calls her name.

And so the Tower becomes the one who recognizes the Risen One—because she, too, has risen.

Initiation and the Naming of the Beloved

The Gospel of the Beloved Companion, a mystical text of contested provenance, goes one step further. It implies that “Magdalene” may not only be a title but also a commissioning—the mark of one who had entered into conscious union, whose love and understanding allowed her to receive the transmission Jesus came to offer.

In this text, the beloved companion is not a shadowy disciple but the Magdalene herself, named not for where she came from, but for who she had become. And in this naming, we are offered a mirror.

Because Magdalene is not just Mary’s name.

It’s a name we can grow into.

It names the part of us that watches without turning away.

The part that anoints the dying.

The part that waits at the tomb.

The part that sees the Risen One—not because it hoped he’d return, but because it had never left.

Implications for Holy Week and Beyond

Rethinking “Magdalene” changes how we enter Holy Week.

It invites us to see not just Jesus’ Passion but ours. The initiatory path of descent, burial, stillness, and emergence is not only his story—it’s the pattern of transformation available to all who watch with the Magdalene gaze.

If Magdalene is a title, then her story is also our vocation.

To be Magdalene is to become tower-hearted.

To root deep enough to stay.

To see clearly enough to name.

To love fiercely enough to rise.

Before you vanish back into the illusion—smash that LIKE or SHARE button like you're breaking open an alabaster jar. One small click, one bold act of remembrance.

And if this stirred something in your chest cavity (or your third eye), consider a paid subscription. Or a one time donation by It keeps the scrolls unrolling, the incense smoldering, and the Magdalene movement caffeinated. ☕️🔥

WHOAH. Chills! “The part that sees the Risen One—not because it hoped he’d return, but because it had never left.” I love this post. When I was little I wanted to have a daughter and name her Magdalene, I thought it was so beautiful. I was talked out of it, I don’t even know by who, because “it just meant from Magdala.” (I had a SS teacher tell me she was a former prostitute—fun learning what a sex worker is in SS—but when I asked my mom about it, she said it wasn’t true. “Even if it was,” she said, “Jesus healed her and don’t we believe his healings are entire and complete?”) Now I’m back to wanting to have a daughter named for the Tower. (I’m not having a daughter or kids at this point —that I know of) Thanks for another inspiring and educational post.

Of course, Jesus was powerful & sure of his faith, but in his human life he was kind of a lone wolf — it’s good that he had a companion, Mary Magdalene, who could understand him & his teachings. I like to think that gave Jesus some comfort.🌹